When I started to think about this post, it was not easy for me to find a clear way to explain it. This has been a long and hard project, involving a lot of teams and processes, and explaining what we have now and why, could be complex without previous knowledge of our flows, methodologies, technologies and general context. This is the reason why I decided to explain how our deployment flow has evolved with the time by writing a series of posts to explain individually every step we made and all the problems we encountered along the way.

In this first article, I will share with you what was our starting point. How we were working and why we decided to improve this flow.

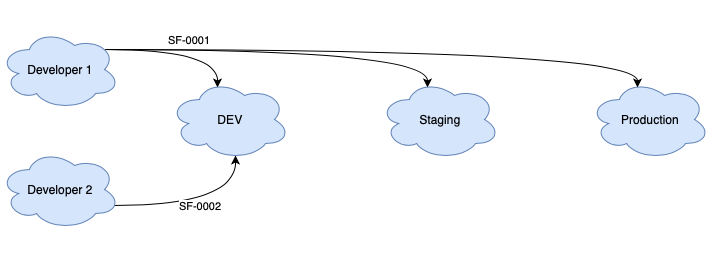

In the very early stage of our Salesforce team here in Ebury, the team was formed only by a couple of developers and a QA engineer. It was an easier time where all the developments were agreed by the full team; each member knew what their colleagues were working on, and the conflicts were very few and quick and easy to resolve.

Every developer had their own sandbox (or several ones in case we were working in stories related to different projects) and, when the development was finished and the code review approved, the code was moved into DEV sandbox (the one used for testing) using changesets. At the same time, every story was developed in a separate branch and, after PR approval, it was merged into the dev branch. You can realise we are using VCS only for code review and for auditing, but not for deployments.

OK, let’s stop here and think why this worked and why this cannot work at scale.

It is not a bad flow, keeping different sandboxes for development and other ones for testing and staging, as you can see in the next picture:

Let’s enumerate the different problems we faced:

- Repository is not the source of truth. This is probably the key point for almost all of our problems, and the most important difference between Salesforce development and the development in any other technology. We cannot trust that the code in the repository is accurate to the orgs, and that is something we cannot allow.

- Changesets are painful. If you are reading this article surely you have worked with changesets at some point. You already know how manual and slow it can be adding changesets, uploading them into a different sandbox (sometimes this can take reeeeally long), deploying, checking something is missing, going back to the source sandbox, cloning it, deploying it again, and all kinds of painful stuff. This can work for little changesets, but when you are deploying hundreds of components, this is worthless.

- Resolving conflicts. What happens if you are modifying some file which is also modified by another developer? We have two options: conflicts or not. If we have conflicts, the developer who faced them has to resolve them, compile the files again in the sandbox, clone the changeset and deploy it again. It could look like not much work… but the problem now is that we have code in our platform which is not related to us. If that other story had new fields, objects, and so, everything has to be created also in your org to be able to continue. And what happens if we have no conflicts? This could be the happy path, but is not, and here is the next point: code overwriting.

- Code overwriting. You just finished your development, the PR is ok and you merged it. Great! Let’s deploy it into dev sandbox, it’s QA time… or not. There is a possibility that when you deployed your changeset into dev, if you have modified the same file another developer did, and as you don’t have those changes in your org (you had no conflicts in the PR, how could you know?), you have deployed a different version of that file and the changes the developer did are now no longer there. We have several workarounds for this, but the communication is the most important point here. If you know what the other developer is doing, mainly because you are reviewing all their changes, then you can anticipate to these conflicts. However, in my experience this step was commonly missed.

- Dependencies: What happens if you pull some dev changes into your code to avoid overwriting but later your story is ready before the other one? You cannot deploy your changeset! This is because your changeset also has changes which are not in the target org, so your story is ready to be deployed into staging/prod, but the deployment is stopped until the other story is also finished. This is frustrating.

- Automation: Changesets are not considered for CI, and there is no easy way to use them from the command line.

- File removal: You cannot remove files using changesets, so you have to search for alternative ways to do it.

Probably I could add some more issues to this list, but I have focused on the main ones.Before finishing: if you are thinking about how great changesets are, I don’t want to wake you from your dream. I know changesets are great for non-developers or people starting in Salesforce, they are easy to use and to understand, and you can do everything through a UI. However, since the moment you start working in more complex projects, involving hundreds of files, dozens of developers, multiple phases and integration with external systems, you need to (must) think about taking a step forward into the CI world.

I hope I’ve been clear enough conveying the problems we had and the reasons for a change. In the next post, we will talk about the different possibilities we were analysing and take a detailed look at the direction we chose (spoiler alert: sfdx).